Evaluators |

Plan: Choosing methods

Choosing an evaluation design

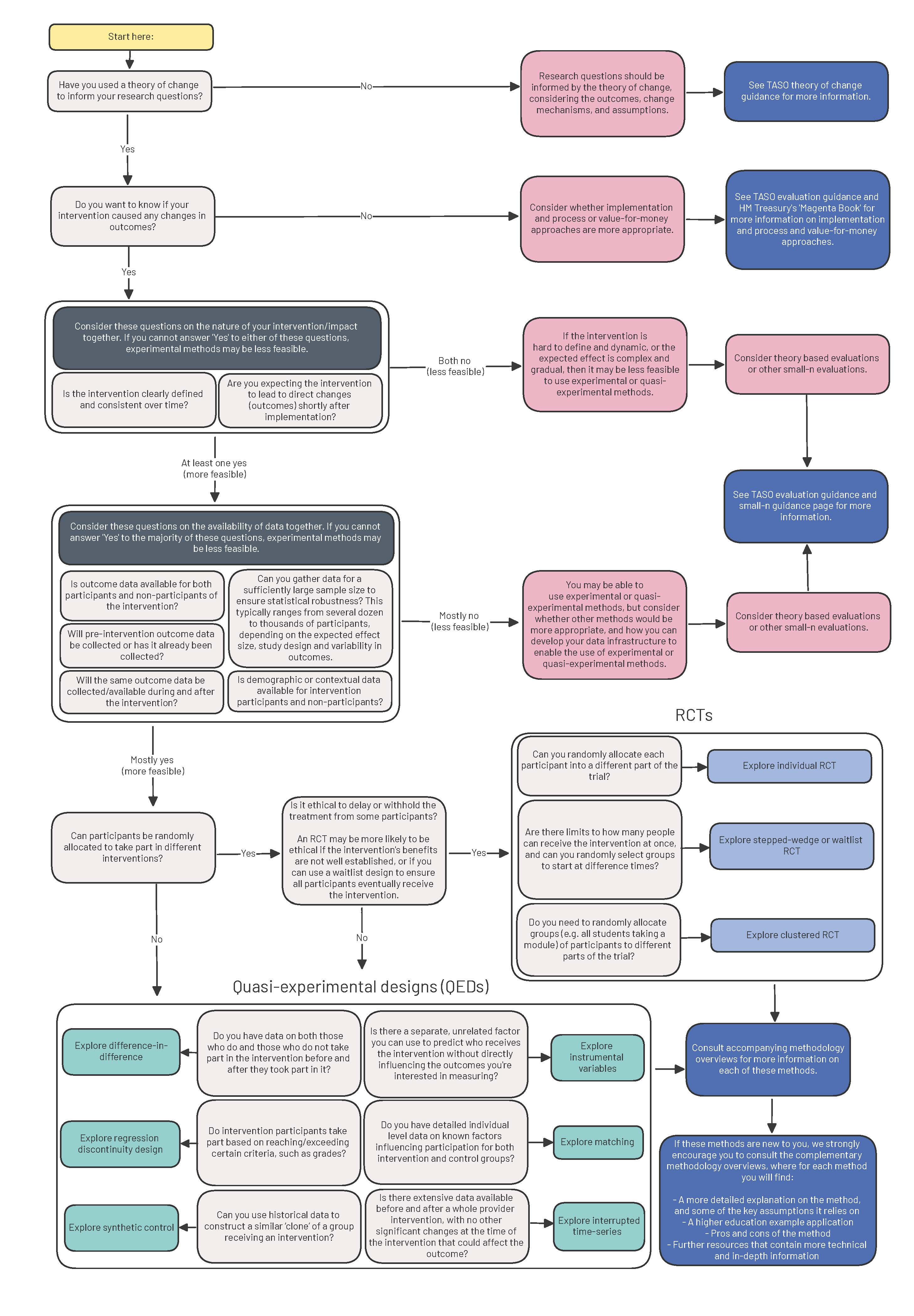

When choosing an evaluation design, there are many factors that will influence your decision, including the nature of the intervention, the availability of data, and any ethical considerations.

Production of type 3 (causal) evidence will often entail using experimental (i.e. a randomised controlled trial, RCT) or quasi-experimental (e.g. difference-in-difference, or regression discontinuity design) methods. The questions in Figure 1 will help you consider which experimental or quasi-experimental methods would be most appropriate and feasible for your evaluation.

Planning the analysis

Resourcing checklist

Data

Do you know what data you need to collect?

Do you know where the data you need is located?

Is the data spread across multiple systems?

Is the data accessible?

Is the data available for the timeframe you need it?

People

Do you know who is going to collect the data, either by obtaining it from the data repository or, for surveys and interviews, obtaining it directly from participants?

Do you know who is going to analyse and interpret the data?

Do you know who is going to write up the analysis?

Systems

Are the required privacy notices in place?

Do you have or need ethical approval to gather the data or conduct the analysis? Note: if you are publishing a report (and we strongly encourage you to do so) then you will require some form of ethical approval to conduct the evaluation.

Writing an analysis plan/trial protocol

A research protocol (also known as an analysis plan or trial protocol) is a written document that describes the overall approach that will be used throughout your intervention, including its evaluation.

A research protocol is important because it:

- lays out a cohesive approach to your planning, implementation and evaluation

- documents your processes and helps create a shared understanding of aims and results

- helps anticipate and mitigate potential challenges

- forms a basis for the management of the project and the assessment of its overall success

- documents the practicalities of implementation.

Reasons for creating a research protocol include:

- Setting out what you are going to do in advance is an opportunity to flush out any challenges and barriers before going into the field.

- Writing a detailed protocol allows others to replicate your intervention and evaluation methodology, which is an important aspect of contributing to the broader research community.

- Setting out your rationale and expectations for the research, and your analysis plan, before doing the research gives your results additional credibility.

The protocol should be written as if it is going to end up in the hands of someone who knows very little about your organisation, the reason for the research, or the intervention. This is to future-proof the protocol, but also to ensure that you document all your thinking and the decisions you have made along the way.

TASO has useful templates for researchers and evaluators writing protocols, including:

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is an important component of any research or evaluation where any of the following are true

- Different students take part in different versions of an activity due to randomisation or selection, and

- The results of the evaluation will be made publicly available

The requirements of the APPs to plan, carry out and publish the results of evaluation mean that ethical approval should be sought.

This presents an opportunity for ethics review boards to set up a dedicated process for evaluation of APP-related activity, which, when using data that is routinely collected or involving the analysis of historical data, is likely to be lower risk than when collecting new data.

A dedicated APP ethical approval process would likely need to consider the following:

- Distinguishing between evaluation that uses data that is routinely collected (i.e. institutional data) and evaluation that requires the collection of new data.

- What outcomes will be tested and the analysis methods used.

- Steps to plan for qualitative data collection (e.g. interviews or focus groups) for implementation and process evaluation (IPE).

Dr Matt Horton at the University of Wolverhampton has set up a dedicated panel for ethical approval of APP work to encourage evaluation in this space.

The purposes of the panel are to improve responsiveness (applications are reviewed on a monthly basis), simplify the application process (reducing the form to questions only relevant to the APP) and to provide a standardised participant information and consent form.

The application form collects the following information

- the theory of change for the intervention

- staff involved in the evaluation

- the timeframe of the evaluation

- an outline of the research questions

- the type of evidence that will be obtained

- the relevant stage in the student lifecycle (access, success, progression)

- how data will be analysed and disseminated

- whether relevant staff have or need Disclosure Barring Service (DBS) certificate (e.g., for pre-entry work).

- how data will be kept secure and confidential

The development of a single APP ethics board makes it easier for the responsible manager to support staff in submitting approvals. Further, the form also collects information that can be used for the OfS evaluation self-assessment tool.

TASO’s Research Ethics Guidance Document provides detailed advice on how to conduct research/evaluation safely and ethically, covering a range of common ethical issues.

It is worth saying at the outset that ethical scrutiny is not intended to stop good research/evaluation, but it is intended to:

protect the human rights of participants in research/evaluation

ensure that risks are considered and mitigated and that harms do not disproportionately fall on one social group

maintain society’s confidence in the ethical self-regulation of the field

protect practitioners from claims of unethical behaviour.

We hope it is clear that ethics cannot be subordinated to researcher/evaluator convenience nor to the additional costs and resources that ethical research/evaluation might incur.